A few weeks ago, the group behind the NHL’s Seattle expansion franchise that will begin play in the 2021-2022 season revealed that the team will be named the Seattle Kraken. Even though the Kraken will be the first NHL franchise to make the city its home, Seattle hockey history goes back more than a century. In today’s post, I thought it would be fun to take a look at some of that history as a way to both honor the past and connect it to the excitement for the future.

Note: This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link and subsequently make a purchase from the linked website, I may receive a commission. The reviews and recommendations on this website are based on my own personal experience and research, and are not influenced by my affiliate status. I will always give my honest opinions to help you make informed decisions. And I always try to find the best deal for you whenever I recommend a product or service. To read the full disclosure statement, click here.

In The Beginning…

Way back in 1915, Seattle got its first professional hockey team, the Metropolitans. The team was part of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, which operated from 1912 to 1924 and was a rival to the National Hockey Association (the predecessor to the NHL).

The PCHA was a groundbreaker in many ways. It was the first Canadian hockey league to add US-based teams; the Metropolitans were the second of three American teams to play in the league, starting one year after the Portland Rosebuds and one year before the Spokane Canaries (love that name).

The league also introduced the use of goal creases, blue lines, the forward pass, and league playoffs. Hockey was a very different game a hundred years ago, obviously.

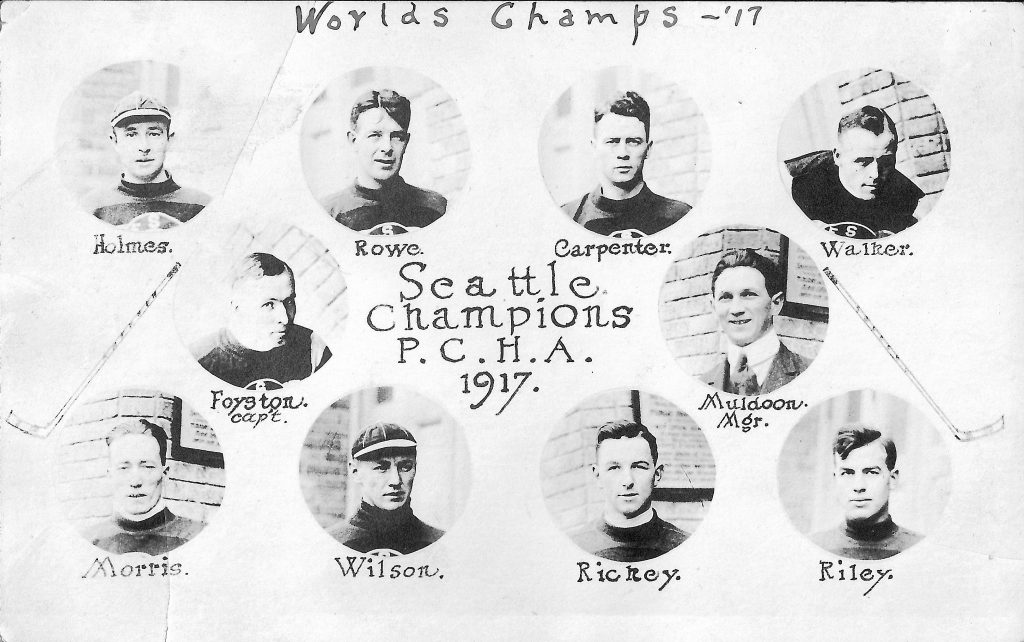

As for the Metropolitans, they also have an important place in history despite only lasting for nine seasons. In 1917, the Metropolitans  (pictured) became the first US team to win the Stanley Cup, beating the Montreal Canadiens three games to one. The entire series was played at the 4,000-seat Seattle Arena.

(pictured) became the first US team to win the Stanley Cup, beating the Montreal Canadiens three games to one. The entire series was played at the 4,000-seat Seattle Arena.

In an interesting side note, the Canadiens, who were the defending champions, must have been very confident going into the series, because they didn’t bring the Stanley Cup with them to Seattle. The Metropolitans wouldn’t get the trophy they had earned until several months later.

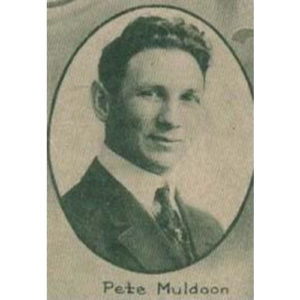

Two years later, the Metropolitans and Canadiens would meet once more to play for the Stanley Cup, again in Seattle. With the series tied after five games (two wins each, plus a tie), both teams were struck by the flu pandemic. Montreal only had three players who would have been able to play in the sixth and deciding game, so team manager George Kennedy told Seattle’s manager, Pete Muldoon (below), that  Montreal was forfeiting the series. Muldoon refused to accept the Cup by forfeit, feeling that it wasn’t fair to “win” it that way, so the last game was cancelled and no winner was declared.

Montreal was forfeiting the series. Muldoon refused to accept the Cup by forfeit, feeling that it wasn’t fair to “win” it that way, so the last game was cancelled and no winner was declared.

Here’s another tidbit – the only other time in the Stanley Cup’s history that it wasn’t awarded was in 2005, because the 2004-2005 season was cancelled due to a lockout. That, of course, means that 1919 is the only time that the Cup wasn’t awarded after playoff games were played.

Sadly, after the 1923-1924 season the team lost its lease when the owners of the Seattle Arena decided to turn the building into a parking garage. Notwithstanding the irony of potentially inspiring a future Joni Mitchell song, this was not a good thing. With the Metropolitans’ owners unable to get financing to build a new arena, the team folded.

Even though they were around for just nine seasons, the Metropolitans left an indelible mark on hockey. Not only for being the first US-based winner of the Stanley Cup, but also for their amazing barber pole-style sweaters. The black and white team picture above doesn’t really do them justice, but if you’re interested in seeing (and perhaps purchasing) a beautiful and authentic reproduction that – fittingly – is made in Seattle by a local company, you can check them out here.

No doubt, the loss of the Metropolitans created a void in Seattle. The city wouldn’t be without hockey for very long, though.

One Home, Many Teams

The Seattle Arena had been the city’s only artificial ice rink, so it was going to take a new rink being built to allow Seattle to have hockey again. That happened in 1928, when the newly-constructed Civic Arena (also known as Mercer Arena) hosted its first game. Pete Muldoon, the former manager of the Metropolitans, was one of the founders of the Pacific Coast Hockey League (PCHL), a new minor pro league that began play in the 1928-1929 season.

In addition, Muldoon was a part-owner of the Eskimos, the league’s Seattle franchise. The PCHL didn’t last long, folding after just three seasons in 1931. Once again, the hiatus for Seattle hockey would be relatively short.

The next go-around was again as a charter member of a new minor pro league. The Sea Hawks were Seattle’s entry in the Northwest Hockey League (NWHL), which launched in the 1933-1934 season. Frank Foyston, a former Metropolitans player who was later inducted into the Hall of Fame, was the manager for most of the team’s first four seasons. He was fired at the start of the third season, but was rehired after the team lost seven of its first 10 games. He ended up leading them to the league championship that season.

The Sea Hawks were bought before the 1940-1941 season and the team’s name was changed to the Olympics. They would only play under that new name for one season, though. Both the franchise and the PCHL went under after the 1940-1941 season.

A second version of the PCHL – unrelated to the first – began play in the 1944-1945 season. This was an amateur league for several years, but after the 1947-1948 season, it transitioned to professional status. Seattle’s franchise, the Ironmen, made that transition as well.

Prior to the 1952-1953 season, the PCHL changed its name to the Western Hockey League (WHL) – no relation to the current WHL of major junior hockey, though. The Ironmen followed suit and became the Bombers, but with attendance down in the early 1950s, team owner Frank Dotten was having financial difficulties. The team suspended operations for the 1954-1955 season.

The franchise rejoined the league the following season with new ownership, and yet another name change, this time to the Americans. This name would last all of three years, before the franchise would finally get a stable identity.

The owners changed the team name to the Totems before the 1958-1959 season. That’s the name that would stay with the franchise for  the rest of its existence, with its last season being 1974-1975. The years from the late 1950s through the late 1960s were the team’s best, with the Totems winning the WHL championship three times and making the finals two other times in a decade-long stretch. Additionally, two Totems players won the league’s MVP award a total of five times (four for Guyle Fielder, one for Bill MacFarland).

the rest of its existence, with its last season being 1974-1975. The years from the late 1950s through the late 1960s were the team’s best, with the Totems winning the WHL championship three times and making the finals two other times in a decade-long stretch. Additionally, two Totems players won the league’s MVP award a total of five times (four for Guyle Fielder, one for Bill MacFarland).

In 1964, the Totems began playing their home games at the brand-new Seattle Coliseum (later known as Key Arena). This made sense for a team that was drawing well at the gate; the Coliseum seated over 12,000 for hockey, compared to roughly 4,100 at Civic Arena.

Unfortunately, after being a dominant force for a decade, the Totems fell into mediocrity or worse for their remaining years. The WHL folded after the 1973-1974 season, and the Totems would play just one more season in the Central Hockey League before folding as well.

And so, since 1975, no professional hockey team has played its home games in Seattle. That doesn’t mean, though, that the city – and Civic Arena – were done with high-level hockey.

Junior League Party

After a couple years without hockey, Seattle, and Civic Arena, had a team again starting in the 1977-1978 season when the Kamloops Chiefs moved from British Columbia and became the Seattle Breakers. The Breakers were a major junior team in the Western Canada Hockey League, which was renamed a year later as the Western Hockey League – the same WHL that we know today.

Over the franchise’s first eight years in Seattle, the Breakers produced a handful of players that would go on to have solid NHL careers: Ryan Walter, Tim Hunter, and Ken Daneyko are the most notable. In general though, the team was pretty mediocre.

That might be why, when new owners took over before the 1985-1986 season, they decided to go with new branding, renaming the team  the Thunderbirds. Over the course of the last 35 years, the franchise has made three trips to the WHL championship, winning once. Not dominant, but certainly better than it was as the Breakers. Several Thunderbirds have distinguished themselves in the NHL: Patrick Marleau, Mathew Barzal (right), Petr Nedved, Chris Osgood, and Brenden Dillon, among others.

the Thunderbirds. Over the course of the last 35 years, the franchise has made three trips to the WHL championship, winning once. Not dominant, but certainly better than it was as the Breakers. Several Thunderbirds have distinguished themselves in the NHL: Patrick Marleau, Mathew Barzal (right), Petr Nedved, Chris Osgood, and Brenden Dillon, among others.

Beginning in 1989, the Thunderbirds would play some home games at Key Arena, but still called Civic Arena their main home until 1995, when they moved to Key Arena full time. However, that building was remodeled in the 1990s and the new configuration actually made it worse for hockey: many of the lower bowl seats had obstructed views, and the scoreboard hung off center over the ice.

And so, in 2008, the Thunderbirds moved to a nice new home in the suburb of Kent, the ShoWare Center. I went to a game there several years ago (Thunderbirds vs. Kelowna Rockets) and I was impressed; it’s a great place to see a game. The only downside was Kelowna’s hideous uniforms. 😉

Third Time’s The Charm

A lot of people may not be aware, but Seattle has had a couple near-misses with getting an NHL franchise in the past. The first began in 1974, when the Totems owners applied for and received an NHL expansion franchise, slated to begin play in the 1976-1977 season. However, the owners kept missing financing deadlines along the way, and in 1975, the NHL pulled the would-be expansion franchise from Seattle.

Fast forward to 1989. This one has a juicier back story, I have to say. The NHL announced that the league would be expanding in the 1992-1993 season. There were two groups interested in getting a franchise for Seattle. One included Chris Larson, a wealthy Microsoft employee, and Bill MacFarland, a former Totems player and coach. The other group was led by Bill Ackerley, whose father was the owner of the NBA’s Seattle Supersonics.

The two groups decided to join forces, and unlike the 1970s effort, everything about their bid seemed to be going well – the financing was in place, and the league was very enthusiastic about Seattle. The group – Larson, MacFarland, Ackerley, and Ackerley’s financial advisor – were scheduled to meet with the NHL Board of Governors in December, 1990. In a move that was a complete surprise to Larson and MacFarland, Ackerley and his financial advisor asked to speak to the Board separately first.

This happened literally moments before all four were going to make their presentation. While Larson and MacFarland waited outside the conference room, Ackerley and his financial advisor went in and told the Board that they were officially withdrawing the group’s bid for a franchise. They then scurried out through a different door so they wouldn’t have to walk by Larson and MacFarland.

Larson and MacFarland were in shock, of course, but they had to go in and instantly try to make the case for a franchise anyway – not an easy thing to do on the fly. Even without Ackerley, they still had the finances, but having the ownership group splinter so dramatically was a pretty bad look, and probably was a huge part of why Larson and MacFarland’s bid was unsuccessful.

Interestingly, it was just a few years later that the Seattle Coliseum (pictured) – home to the Supersonics, and the arena where the group’s  expansion franchise would have played – underwent the renovation that I mentioned earlier. That renovation basically turned the building into one that worked well for basketball, but was unqualified for NHL hockey.

expansion franchise would have played – underwent the renovation that I mentioned earlier. That renovation basically turned the building into one that worked well for basketball, but was unqualified for NHL hockey.

Some people think (justifiably, in my opinion) that Ackerley’s whole purpose in getting involved with an NHL expansion bid, and the subsequent Coliseum renovation, was actually to prevent an NHL team from coming to Seattle. That way, the Supersonics would have less competition and more power when it came to things like lease negotiations and fan spending.

If so, it worked, but only temporarily. Ackerley’s father sold the Supersonics in 2001 to Howard Schulz, of Starbucks fame. He sold the team in 2006, and in 2008 it was moved, becoming the Oklahoma City Thunder.

Meanwhile, the Coliseum, which is owned by the city of Seattle, has undergone a massive redevelopment costing nearly $1 billion. Now known as Climate Pledge Arena, it is scheduled to open in the summer of 2021 and will be the home of the Kraken.

Let’s Get Kraken!

In barely more than a year, there finally will be an NHL team playing its home games in Seattle. It’s always exciting when the NHL arrives in a market for the first time; we saw that with Las Vegas a few years ago. Somehow, though, it feels especially satisfying to see the excitement in Seattle. Simply put, after supporting so many different teams of varying levels over the years, and being jilted a couple times by the league, the city deserves an NHL team.

And it looks like the fans are all in. The Kraken received 32,000 deposits for season ticket packages, and currently have an additional 51,000 people on a waiting list. After the team name announcement, Kraken merchandise sales exceeded the Vegas Golden Knights’ sales following that team’s introduction by more than 50%.

That’s impressive, but not completely shocking. The Kraken organization really did their homework with the branding. Having an “S” for the primary logo is an homage to the past, since the Metropolitans had an “S” on the front of their sweaters too. With the Space Needle as the secondary logo and the ocean-inspired color scheme, everything ties together thematically. In short, the Kraken have a pretty awesome look. If you haven’t seen it – or if you want to pick up something to represent the team – you can check out their stuff here.

I’m looking forward to seeing the Kraken develop a healthy rivalry with the Vancouver Canucks. I’m also curious to see what kind of roster the team puts together in the expansion draft, and if they can have the same kind of success in their first season as the Golden Knights did.

Seattle has a long and interesting hockey history. Now that it finally has an NHL team in the Kraken, that history will take on new dimension.

Clean Ice

I hope you enjoyed this post. I’d love to hear from you. Did you know that Seattle’s hockey history was so long and varied? How do you think the Kraken will do when they start playing next year? What players do you think they might get in the expansion draft? And what do you think of the team name and uniforms?

Please send me your feedback, or any questions – thanks!