With Father’s Day coming up this weekend, I decided this would be an appropriate time for a post about some of the many hockey father and son combos that we’ve seen over the years. I’ve always had the sense that there are more cases of fathers and sons playing in the NHL than in other major professional sports leagues. The frequency with which it happens in hockey is fascinating to me.

A couple years ago, I wrote a Father’s Day post about my dad, which you can read here. In that post, I mentioned that I had some ideas about why dad/son combos are so common in hockey, and promised to touch on those ideas in a later post.

Well, this isn’t that later post. I do still want to explore the reasons, but for now I’m punting that topic down the road a bit (again). Today, I just want to look at the frequency of the father/son trend in hockey, and highlight some of the most interesting combos from both the past and the present.

By the Numbers

Let’s start with some basics. From when the NHL started in 1917 through the end of the 2019-20 regular season, there had been 191 NHL players that had a son who went on to play in the NHL himself. And since some players had more than one son that played in the league, there were 212 sons in those father/son combos.

The numbers just keep growing every year, too. After accounting for players that made their league debut in the 2020-21 season, the NHL’s father/son club now stands at 197 dads and 220 sons.

That’s pretty crazy, because that means that more than two percent of players that have played in the league have had a son go on to play in the league themselves. Sure, there are lots of cases where one or both generations only played a game or two in the NHL, but still…

There have only been two families – the Howes and the Hulls – where both a father and son have been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as players. I’ll talk about both of those families in a minute, but it raises an interesting question – could there be any instances of this in the future involving current players?

Personally, I think it’s unlikely. As far as I know, the only current NHL player whose dad is already in the Hall of Fame as a player is Paul Stastny, whose father Peter was inducted in 1998. Paul is a good player, but I can’t see him making the Hall of Fame.

The only other family that might have a chance is the Tkachuk family. That might sound strange since dad Keith retired in 2010 and isn’t in the Hall of Fame yet, but given that he had 538 career goals and was one of the premier power forwards of his generation, I think he’ll get there eventually. The question is, will either of his sons Matthew or Brady put together a career that gets them in?

Personally, I don’t think either of them is on a Hall of Fame trajectory yet. Both are good players, and important pieces of their respective teams, but if you take their numbers so far in their careers and project them out, neither would reach 400 goals until they had played nearly 1300 games. That’s a very long career (especially given the physical style both of them play), and that 400-goal threshold still is not any kind of guarantee for Hall of Fame consideration.

So, I think the Howes and Hulls will remain the only father/son player combos to make the Hall of Fame for the foreseeable future. Still, with the ever-increasing instances of sons following in their fathers’ footsteps to the NHL, I’m sure we’ll see another pair in the Hall eventually.

Howe Do You Do?

A popular topic for debate among hockey fans is the question of who should be considered the “First Family of Hockey.” There are plenty of viable candidates, and it really depends on the criteria that you consider the most important. Are you focused on how many family members reached the top levels of hockey, how many generations, how many different roles in hockey members of the family filled, how good the best members of the family were, or how broad and lasting the family’s impact on the game has been?

Naturally, any “First Family” candidate is almost certain to include a father/son combo, and that brings us to the Howes. Gordie Howe was known as Mr. Hockey, and that nickname expresses pretty clearly his importance to the game. He would be a legend on his own, but the legend expanded as two of his sons, Mark and Marty, played professionally as well.

known as Mr. Hockey, and that nickname expresses pretty clearly his importance to the game. He would be a legend on his own, but the legend expanded as two of his sons, Mark and Marty, played professionally as well.

After playing 25 years with the Detroit Red Wings, Gordie retired in 1971 at the age of 43. At the time, he was the undisputed greatest player in NHL history up to that point. He won six Art Ross trophies as the league scoring leader, six Hart Trophies as MVP, four Stanley Cups, and at the time held the NHL career records for goals, assists, and points. The stat that I find most amazing about Gordie Howe is that he finished in the top five in scoring for an astounding 20 consecutive seasons, from 1949-50 through 1968-69. Nobody else has ever done that, and I don’t think anyone ever will.

WHA Happened?

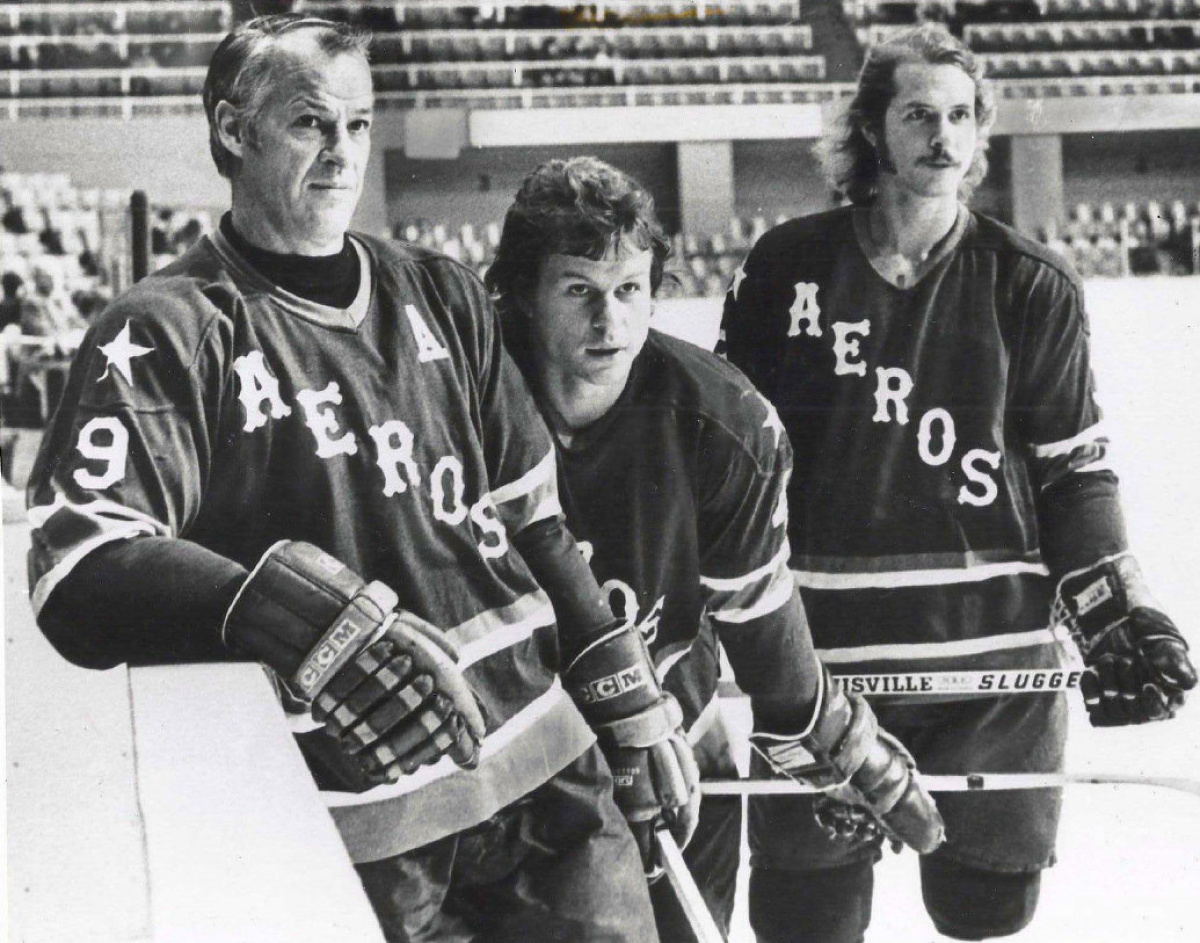

In 1973, the Houston Aeros of the WHA came calling to sign Mark and Marty. Gordie had retired from playing two years earlier and had found a front office job with the Red Wings unfulfilling. Half-jokingly, he told the Aeros that instead of two Howes, they should sign three. That set the ball rolling, and starting with the 1973-74 season, Gordie played with his sons for seven seasons – six in the WHA (four with the Aeros, and two with the Whalers), and one final season in the NHL after the Whalers were one of four WHA teams absorbed into the NHL before the 1979-80 season.

The Howes are the only family in NHL history to have a father play in the league at the same time as his son, never mind two sons, and never mind on the same team. And while I haven’t verified this, I’ll go out on a limb and say that they were the only family to do those things in the WHA too.

For the WHA, getting the three Howes on the ice, especially for the same team, was a huge win. Hockey was a foreign concept in Houston, but Gordie probably brought a more recognizable name than any other hockey player could have. That, combined with the novelty of his playing with his sons, helped the Aeros market the team far better than they could have otherwise.

But the Aeros signing all three Howes wasn’t a gimmick. The bottom line is, they could play. Gordie won the WHA’s MVP award (named the Gordie Howe Trophy) in their first season with the Aeros, finished in the top 10 in league scoring four times, and averaged over a point per game in six WHA seasons. The Howes led the Aeros to two league championships, and lost in the finals two other times (once each with the Aeros and Whalers).

Mark was named rookie of the year in 1973-74, and made the first all-star team once and the second team twice in six WHA seasons. Impressively, he made the second team as a left wing in 1973-74, then as a defenseman in 1976-77, then switched back to left wing, where he made the first team in 1978-79. Mark also had two top-ten finishes in WHA scoring, and like Gordie, averaged over a point per game in his WHA career.

Marty Howe, though not a star like Gordie or Mark, was a solid player during the family’s six years in the WHA. He played in 449 WHA games over those six seasons, which is actually slightly more than Gordie or Mark. Along with his dad and brother, he played for Team Canada in the WHA’s 1974 Summit Series against the Soviet Union.

An Ending, and a New Beginning

The Howes remained with the Whalers when the team joined the NHL before the 1979-80 season. That would be Gordie’s last season. He played in all 80 games, finishing seventh on the team in scoring. By the time the season was over, he was 52 years old.

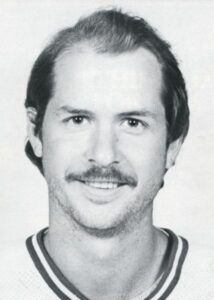

As for Mark and Marty, their playing careers took different trajectories, especially after joining the NHL. For the first three seasons that the Whalers were in the NHL, Marty (at right) saw limited action, playing mostly in the minor leagues. Then he was traded to Boston before the 1982-83 season, where he played one season. Interestingly, he was relegated to the minors for most of the previous three seasons by the Whalers, who were one of the weakest teams in the league. Yet with the Bruins, who had the league’s best record in 1982-83, he was a regular in the lineup, playing in 78 games. After that season, he was traded back to Hartford, where he again played the full season at the NHL level. In 1984-85, though, he was back to shuttling between the Whalers and the minors, and retired following that season.

Whalers, who were one of the weakest teams in the league. Yet with the Bruins, who had the league’s best record in 1982-83, he was a regular in the lineup, playing in 78 games. After that season, he was traded back to Hartford, where he again played the full season at the NHL level. In 1984-85, though, he was back to shuttling between the Whalers and the minors, and retired following that season.

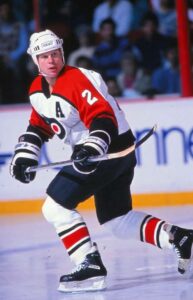

Mark (at right, below) was a star in the WHA, and that just continued into his NHL career, which lasted from 1979-80 through 1994-95. If anything, he got even better after moving to the NHL. He stopped moving between positions, and immediately established himself as one of the best all-around defensemen in the league. Before the 1982-83 season, the Whalers traded Mark to the Flyers, where he played 10 seasons before going to Detroit for the last three seasons of his career.

In my opinion, Mark Howe is one of the most underappreciated players to ever play the game, and certainly belongs on any list of the best American-born players of all time. He could do it all as a defenseman at both ends of the ice. He was an excellent skater, had great hockey sense, and was cool under pressure. He had the rare ability to control the pace of a game, similar to Niklas Lidstrom, though I would say Howe was a little more physical and offensively aggressive.

American-born players of all time. He could do it all as a defenseman at both ends of the ice. He was an excellent skater, had great hockey sense, and was cool under pressure. He had the rare ability to control the pace of a game, similar to Niklas Lidstrom, though I would say Howe was a little more physical and offensively aggressive.

Howe was named a first-team all star three times in the NHL. Unfortunately his best years overlapped with those of Ray Bourque and Paul Coffey, so he never won the Norris Trophy as the league’s best defenseman, but he finished second in voting three times, and was in the top ten five other times. He holds the NHL career record for shorthanded goals by a defenseman with 28. That record should be safe for a while, as he has more than double what any currently-active defenseman has. Oh, and Howe also won a silver medal with the US team at the 1972 Olympics – when he was just 16 years old.

Mark Howe’s number 2 was retired by the Flyers in 2012. One year earlier, he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, making him and his dad just the second father/son combo to both be in the Hall of Fame as players.

Hull On Ice (And Off Ice)

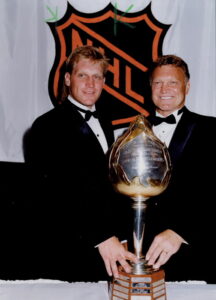

The only other father and son to both make the Hall of Fame as players are Bobby Hull and his son, Brett Hull. As you might expect, they hold some unique records for a father/son combo: only duo to both score 600+ goals in the NHL, 50+ goals in a season, win the Hart Trophy as league MVP, and lead the NHL in goal scoring.

hold some unique records for a father/son combo: only duo to both score 600+ goals in the NHL, 50+ goals in a season, win the Hart Trophy as league MVP, and lead the NHL in goal scoring.

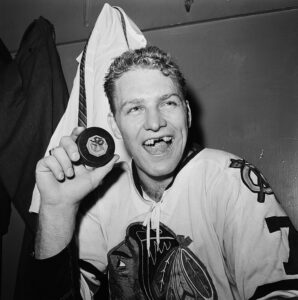

The Golden Jet

Bobby, known as “The Golden Jet” thanks to his blonde hair and blazing skating speed, was one of the most iconic players the NHL has ever seen. Along with his speed and photogenic looks, his legendary slap shot and willingness to talk and sign autographs made him a fan favorite. Like Mickey Mantle in baseball, he was the player that kids pretended to be when they played pickup games.

Bobby Hull’s achievements in hockey are undeniable. He was the best goal scorer of his generation, and won two Hart Trophies as MVP, three Art Ross Trophies as scoring leader, and led the NHL in goals seven times. He also helped the Blackhawks win the 1961 Stanley Cup.

In 1972, at the age of 33, after years of tension with the Blackhawks over money, Hull defected to the Winnipeg Jets of the new World Hockey Association. Hull was the first big name to sign with a WHA team, and the contract was astronomical for the time – $1.75 million over 10 years, plus a $1 million signing bonus. His signing gave the WHA credibility and was the catalyst for a dramatic climb in player salaries in both leagues during the 1970s, as NHL teams had to pay more to keep players from jumping to the rival league.

salaries in both leagues during the 1970s, as NHL teams had to pay more to keep players from jumping to the rival league.

In the WHA, Hull continued to excel, winning two MVP awards, being named to three first and two second all-star teams, and helping the Jets win two WHA championships. Playing a beautiful skill-based style as part of the “Hot Line” with Swedish teammates Ulf Nilsson and Anders Hedberg, he spoke out against the violent goonery plaguing hockey in the 1970s, even staging a one-man, one-game strike in protest.

After retiring a few games into the 1978-79 season, he returned the next season when the Jets joined the NHL. Missing much of the year due to injuries, he was traded that season to Hartford, where he played nine more games as a teammate of the Howes before retiring for good after the season.

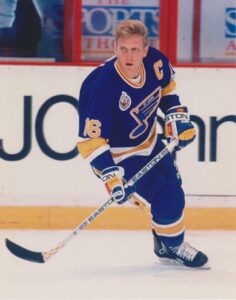

The Golden Brett

Stylistically, Brett Hull, aka “The Golden Brett,” was a different player from his dad. He wasn’t a fast or pretty skater; he didn’t pull fans out of their seats with thrilling end-to-end rushes like Bobby had. Considered a lazy and selfish player early in his career, he was close to the same height and weight as his father, but he didn’t have the elder Hull’s impressive physique.

The thing that Brett did have in common with his dad, though, was the ability to score goals. Brett had a great slap shot like his dad, but what really made him a legendary shooter was his lightning-fast release on snap shots and wrist shots. If the puck came near him, it was off his stick before the goalie had time to get set – often before the goalie was even able to track the puck to Hull.

That brings up another aspect of Brett’s goal-scoring prowess. He had an incredible knack for getting open. He was very smart about sensing when a hole in defensive coverage was about to develop, and he would lurk undetected, temporarily harmless, until just the right moment when that space would open up and he would move in, take a pass, and put it in the back of the net, all in the blink of an eye.

sensing when a hole in defensive coverage was about to develop, and he would lurk undetected, temporarily harmless, until just the right moment when that space would open up and he would move in, take a pass, and put it in the back of the net, all in the blink of an eye.

It wasn’t as flashy as his dad’s signature booming slap shots coming down the wing on a rush, but it was incredibly effective. Brett played with some centers that were excellent passers, especially during his best offensive years in St. Louis, but ultimately he was able to score a lot of goals that other players wouldn’t have because he didn’t need much time or space. His center could put the puck in spots for him that they couldn’t for most players, because Brett had the intelligence and the quick shot release to turn that tiny opening of time and space into a legitimate scoring opportunity.

Only eight players in NHL history have scored 70 or more goals in a season; they achieved the feat a combined total of 14 times. Brett Hull did it three times, making him one of only three players to accomplish it more than once, along with Wayne Gretzky (4x) and Mario Lemieux (2x). He finished his career with 741 goals – more than his dad, and currently fourth all time – and 1391 points. Hull won a Hart Trophy as MVP, a Lester Pearson Award (now the Ted Lindsay Award) for most outstanding player as voted by the players, was a first all-star team selection three times, and won two Stanley Cups (one each with Dallas and Detroit).

Tarnished Gold

So, both Hulls clearly were great hockey players, and Bobby Hull did some really important things for the game. However, I can’t talk about this father/son combo without talking about the dark side, which is that despite his fan-friendly personality, away from the ice, the real-life version of Bobby Hull is very different.

Hull was extremely abusive toward his second wife, to whom he was married from 1960 to 1980. She has spoken about a 1966 incident in which he beat her to a bloody pulp with her own steel-heeled shoe, then hung her over a balcony. In 1978, he threatened her with a loaded shotgun. As if these two instances weren’t bad enough, there apparently were many more violent incidents throughout their marriage, which ended in divorce in 1980.

Hull remarried a few years later, and in 1986 he was arrested for assault and battery against his wife. She later decided to drop the charges, but he was fined and given probation for trying to punch one of the police officers responding to the call.

In 1998, a Russian newspaper published an article with racist, Nazi-sympathizing quotes attributed to Hull. He claimed he was misquoted and threatened to sue, but it’s not clear if he ever did, and the paper stood by its reporting. It’s worth noting that his daughter said that the comments sounded exactly like things her dad would say. Hull’s daughter became a lawyer representing domestic violence victims, a career choice that surely had some roots in the dynamic she saw in her parents’ marriage.

In another post, I wrote about how when I was a kid, before I started playing or following hockey, I only knew the names of a few hockey players; Bobby Hull was one of them. Even though he was retired by the time I got into hockey, he was still a legend in my world view of the sport. When I got older and learned about some of the darker aspects of Bobby Hull, it felt like some of the innocence was retroactively stripped away from my childhood memories. But that’s OK, because I’m an adult and I know that this is bound to happen sometimes as we get older.

For some people, though, that recognition – that all heroes are flawed, but some childhood heroes are too flawed to be deserving of hero status – is too jarring. They can’t deal with it, so they ignore the uncomfortable truth. I guess this is why Bobby Hull is still an official ambassador for the Chicago Blackhawks. To me, that’s shameful, because in continuing to employ Hull in that capacity, the Blackhawks send a clear message that they are OK with his long history of very bad behavior, simply because he was a great hockey player.

Peter, Paul, And… Yan?

As I said earlier, I don’t think the Stastnys will join the Howes and Hulls in having a father and son both in the Hall of Fame as players. However, there is one feat that the Stastnys achieved that makes them unique not just compared to the Howes and Hulls, but any other father and son(s) in hockey history. I’ll get to that in just a minute, but first let’s look at each of the Stastnys individually.

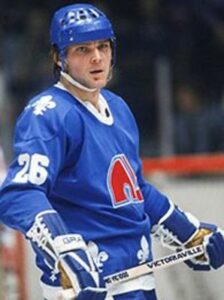

Peter the Great

I said above that Mark Howe is extremely underappreciated; that might be even more true of Peter Stastny. Stastny had more points in the NHL during the 1980s than anyone except Wayne Gretzky, and yet somehow he was never named a first- or second-team all star.

Stastny started his NHL career in the 1980-81 season at age 24, after defecting from Czechoslovakia with his younger brother Anton. Joined the following year by older brother Marian, the three gave the Quebec Nordiques one of the best lines in the league, combining for 300 points in their first season together.

300 points in their first season together.

Peter, though, was clearly the best of the trio, winning the Calder Trophy as rookie of the year, racking up seven seasons with 100+ points, and finishing his NHL career with 1239 points in 977 games. His 1.27 points per game over his career puts him in eighth place in NHL history. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1998.

Stastny was revered in Quebec, and not just for his on-ice exploits. Upon arriving in Quebec, he took it upon himself to learn French, which was appreciated by fans (he later learned English as well). He also obtained Canadian citizenship and played for Canada in the 1984 Canada Cup, after having competed internationally for Czechoslovakia before defecting. Late in his career, after the Cold War ended and Czechoslovakia split up into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Stastny played for his native Slovakia, making him the first player in hockey history to represent three different countries in international play.

After nearly 10 seasons with the Nordiques, Stastny was traded to New Jersey late in the 1989-90 season. Though he was no longer putting up the kind of superstar numbers he had in Quebec, Stastny was still a very effective player and was an important leader as the Devils began building toward contender status. After the 1992-93 season, Stastny signed as a free agent with St. Louis, but only played a total of 23 games in two seasons with the Blues before retiring from the NHL.

Stastny has always been a man of character, willing to take a stand on issues of integrity. After hanging up his skates, Stastny served two terms representing Slovakia as a member of the European Parliament, and was a signatory of the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism. He also spoke out against corruption, incompetence, and the anti-democratic history of the leadership of the Slovak Ice Hockey Federation, even resigning from the Slovak Hockey Hall of Fame and disassociating himself with his former club team (HC Slovan Bratislava) in protest when they didn’t take action.

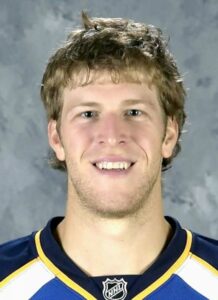

Paul the Good

Paul Stastny is not the player that his dad was, but that’s no slight to him. Paul has had a very good career, and while at age 35 his offensive production has slipped a bit in the last couple years, he is still a solid player who adds value to his team.

Paul played two years at the University of Denver, where he was a standout. As a freshman, he helped the Pioneers win a national championship, winning the WCHA rookie of the year award and being named to the NCAA all-tournament team in the process. In his second year, he led the WCHA and was seventh in the country in scoring; he was named a second-team All American at the end of the season.

second year, he led the WCHA and was seventh in the country in scoring; he was named a second-team All American at the end of the season.

Stastny turned pro the next season, joining the Avalanche – the same franchise his father had played for before the team moved from Quebec to Denver. After eight strong seasons with the Avs, Stastny signed as a free agent with the Blues, returning to the city where he had lived for much of his youth. After nearly four seasons in St. Louis, he was dealt at the trade deadline in 2018 to Winnipeg as a deadline rental. He signed with the Golden Knights that summer, but was again traded to the Jets before the 2020-21 season.

Stastny is currently an unrestricted free agent again, and at 35 years old and with his offensive numbers down the past couple seasons, he’ll almost certainly have to take a pay cut regardless of where he signs. That said, he’ll still generate interest, because he can bring veteran leadership, playmaking ability, hockey sense, and he’s good on faceoffs. Plus he has a history of coming up big in key moments.

As I said earlier, I don’t think there’s any chance that Stastny will join his dad in the Hall of Fame, but he still has been a very effective and well-respected player since entering the league. He also has represented the United States in international play, twice in the Olympics and three times at the World Championships.

Yan the Elder Brother

Paul’s brother Yan Stastny is older by three years, and first reached the NHL one season before Paul. Drafted by Boston in 2002, Yan played two years of college hockey at Notre Dame, then turned pro and played two years in Germany. He returned to North America for the 2005-06 season and, after being traded to Edmonton before the season started, made his NHL debut with the Oilers. He was traded back to Boston partway through the season, where he saw more time at the NHL level.

back to Boston partway through the season, where he saw more time at the NHL level.

For five seasons, Yan went back and forth between the NHL and AHL, spending time with the Oilers, Bruins, and Blues. Beginning with the 2010-11 season, he played the rest of his career in Europe, with stops in Russia, Germany (two more times), Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Austria. He retired after the 2017-18 season.

While he didn’t light the NHL on fire (6 goals and 10 assists in 91 NHL games), Yan’s work ethic and responsible defensive play as a center allowed him to have a solid career in other leagues. And he played for Team USA three times in the World Championships. The first two times were before Paul’s first time playing for Team USA, which means Yan and Peter were responsible for that unique feat that I mentioned earlier – they, later joined by Paul, became the first (and still the only) father and son(s) to represent four different countries in international hockey competition. That’s a record that’ll probably stand at least as long as any father/son records set by the Howes and Hulls.

Pass It On

Well, that brings us to the end of this post, but given that it only covers three families, we haven’t even come close to exhausting this topic. I’ll definitely revisit this again in the future. Maybe it’ll become a Father’s Day tradition.

In the meantime, I’d love to get your feedback! Between the hockey father and son combos in this post, which combination do you think is the most impressive as a whole? Which of the individual players are your favorites? Which have you seen play in person, or would you most want to see? What are your thoughts on the Blackhawks continuing to employ Bobby Hull as a team ambassador given his history of bad behavior – do you think it’s wrong to give him a platform and a spotlight, or do you compartmentalize his off-ice life from his on-ice glory? And finally, who are some of your favorites among the other father/son combos in hockey?

Please leave your comments (and any questions) below. Thanks for reading, and Happy Father’s Day!