Over the past couple weeks, the subjects of racism and hockey have been intertwined as a result of an incident that happened back on Friday, April 3. On that day, the New York Rangers hosted a live fan question and answer session on Zoom with K’Andre Miller, who just signed his first professional contract with the team in March. Sadly, during the chat, someone posted a racial slur in the chat screen hundreds of times within a span of several seconds before the Rangers were able to disable it.

The reaction was quick and loud, as it should be; the Rangers, the NHL, and players from both the Rangers and around the league condemned the disgusting behavior and expressed support for Miller. That was heartening to see, and as many stated, anybody that would do something like this isn’t welcome in the hockey community.

In fact, it’s quite likely that whoever was responsible wasn’t a hockey fan, but rather just was looking for an opportunity to be a jerk. The FBI apparently was already looking into multiple similar instances of Zoom meetings being hijacked – “Zoom bombed” – by anonymous individuals disrupting live meetings with racist comments.

Still, it happened, and it brings up some important questions – namely, where do things stand today with regard to racism in hockey? How much progress has been made over the years in getting racism, and prejudice in general, out of the game? And, will it ever be possible to completely eliminate racism and other forms of prejudice from hockey?

Historical Context

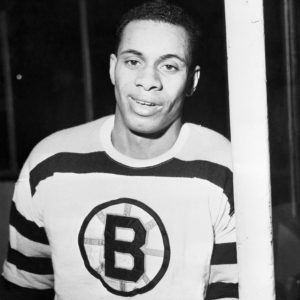

When Willie O’Ree (right) became the first black player to play in the NHL back in 1958, it was more than a decade after  Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. That’s pretty stark, but what stands out even more is that after O’Ree, there wasn’t another black player in the NHL until 1974.

Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. That’s pretty stark, but what stands out even more is that after O’Ree, there wasn’t another black player in the NHL until 1974.

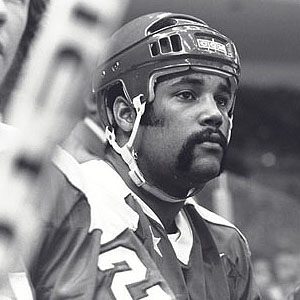

Granted, the demographics at the time probably had something to do with the long gap between black players in the NHL. When O’Ree made his debut, 99% of NHL players were Canadian, and less than two tenths of one percent of Canada’s population was black. In 1974, when Mike Marson became the NHL’s second black player, Canada still provided roughly 91% of NHL players, but the percentage of the country’s population that was black still was only around the 0.2% mark.

Canada’s dominance of NHL rosters has gradually dwindled; the country now accounts for a little under 43% of roster spots. At the same time, the country has grown much more racially diverse in the past several decades. Black citizens now make up 3.5% of the population, and over 22% of Canadians identify as visible minorities.

So yes, there seems to be a logical connection between the scarcity of black players in the NHL into the 1970s and the fact that the source (Canada) of virtually all the players had almost no black people. And likewise, the increased diversity in Canada (which still produces more NHL players than any other country), along with the growth of hockey among minorities in the United States and elsewhere, explain why the numbers of black players in the NHL has gradually increased over the past 40+ years (and especially over the past 20).

The Harsh Reality

Still, while the population demographics might have been a significant factor in why there were so few black players in the NHL and other high levels of hockey, the fact is that the black players that were there faced prejudice when they played. The demographic statistics can’t explain or excuse the bigotry directed at black players: racist taunts from opposing players and fans, dirty play, even death threats.

Mike Marson (right), who in addition to being the NHL’s second black player was also the first black player ever drafted by an NHL club, found his game getting sidetracked because he was sticking up for himself against racial slurs. Other black players, especially  those that played back in the 1970s, have talked about similar experiences, where they had to get into more confrontations with opponents than they wanted. This was sometimes because they were physically challenged more often than white players, and sometimes because they had had enough of the comments and wanted to show that there would be consequences.

those that played back in the 1970s, have talked about similar experiences, where they had to get into more confrontations with opponents than they wanted. This was sometimes because they were physically challenged more often than white players, and sometimes because they had had enough of the comments and wanted to show that there would be consequences.

Something that stands out to me about this, of course, is that hockey is a team game. Probably more than any other sport, hockey players generally are known to stick up for their teammates on the ice. Even today, when fighting in professional hockey has been drastically reduced from the 1970s and 1980s, when someone lays a dirty hit on a player, or tries to rough up a finesse player or a rookie, you’ll frequently see a teammate come to that player’s defense.

It’s jarring to think about the fact that black players back then probably didn’t feel like people had their back when they were on the receiving end of racist comments and dirty plays from opponents. But sadly, they felt that way with good reason. That isn’t to say that the teammates of players like O’Ree, Marson, and others didn’t support them. But support from teammates wasn’t enough, and more leadership could have been shown by others in hockey.

I’ll explain what I mean by that. To put it in simple terms, if a player is the target of comments from an opposing team – whether it’s racial epithets or just run-of-the-mill, “you suck at hockey” trash talk – other people are going to hear it. Players on both teams, officials, and frequently coaches are aware of what’s being said on the ice.

To me, the fact that the first black players in the NHL were subjected to racist remarks on the ice repeatedly says that some people – some of those other players, officials, and coaches – didn’t do anything. Or if they did – say, by reporting the offenders to the league office – then the league didn’t take strong enough action.

People react to consequences. It’s pretty clear that back in the day, not enough people enforced consequences for racist behavior in the NHL, and that goes for other levels of organized hockey too. Because if there were consequences – if officials, teams or leagues had penalized players for racist comments on the ice, for example – then the behavior wouldn’t have been nearly as common back then.

Changing Times

Fortunately, the days when racism in the hockey world was ignored are gone. Things certainly aren’t perfect today, but the culture has changed. If there is an incident, it typically is escalated and dealt with at a team or league level.

Again, though, hockey still has lots of progress to make. And that is probably even more true at lower levels or among fans than among NHL players. Just think about some of the incidents that have made headlines in the past several years: Wayne Simmonds had a banana thrown at him by a spectator at a 2011 exhibition game; a 13-year-old player was on the receiving end of racial slurs during a 2018 tournament; and also in 2018, Givani Smith, who was playing junior hockey for the Kitchener Rangers, got such severe racial harassment and threats on social media during a playoff series that he was given a police escort to the rink for away games. And there have been other incidents, these are just the first ones that came to mind.

However, what is different now compared to Willie O’Ree’s time or Mike Marson’s time, or even compared to the 1980s, is the reaction. Namely, that there was a reaction, where in the old days these stories never would have become stories.

In the case of the fan that threw a banana at Wayne Simmonds, other fans pointed him out to police in the arena; he was charged and found guilty. The 13-year-old player’s teammates came to his defense, and when the story became public, the Washington Capitals were so impressed with the team’s solidarity that they invited them to a game and to meet the Caps players. With Givani Smith, while the people that harassed and threatened him weren’t punished, there was a groundswell of support for him from teammates, coaches, executives, and league officials.

That is the biggest difference between the culture of hockey now and decades ago. Today, the overwhelming majority of people in the hockey world feel strongly enough to speak up and say that racism isn’t OK. The climate has changed so that now when there is an incident involving racism, even if teams or leagues wanted to ignore the incident, the weight of public pressure wouldn’t allow them to. And I’m not saying that they would want to ignore it. I genuinely believe that most teams and leagues these days really do want to make hockey a welcoming sport for everybody.

Looking Ahead

Where does hockey go now with respect to continuing to eliminate racism? Well, I’m not a sociologist, but here’s my take. Hockey has made some progress, but there’s still a long way to go. I think the same is true of society in general.

When it comes to people within the game, I would say that hockey, at least at the higher levels, has the means to change what is considered acceptable, through a combination of carrot and stick. Education and training being the carrot, and real consequences like loss of employment being the stick.

However, there are other people in the hockey world that teams and leagues have less ability to influence, and those are the people in the stands, or at home on their computers. Yes, when someone acts in a racist manner at a game, a team can have them removed, perhaps ban them from ever coming back, and even press charges. But “fans” – whether in the arena or posting on social media from home – have learned and assimilated their worldview through their own upbringing. So while it’s sad to say, I think hockey will always be, at least in part, a microcosm of the larger society.

What About You?

What are your thoughts on racism in hockey? How do you think hockey compares to other sports on that front, and why? Have you ever witnessed or experienced racism in a hockey-related setting, and if so, how did you react?

I’m really interested in hearing what you have to say about this topic – please leave comments or questions below. Thanks!